Facebook’s own data shows that brands have been doing social media wrong for years

Occasionally, just occasionally, Facebook comes out with a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it nugget that marketers really should pay attention to. And in Facebook’s webinars that have been doing the rounds in the US and Europe (coming to APAC soon), two lines really stood out:

“Engagement metrics do not correlate with sales volume” and, “It’s hard to control and plan for earned media.”

Source: Facebook

These shouldn’t be surprising conclusions. PR professionals can attest to the second sentence, while anybody who has worked in social will have inevitably been faced with the question: “We’re getting a lot of likes. What does that mean?”

But when the internet is also inundated with advice from thought leaders telling us that organic social is the path to marketing nirvana and that cutting your marketing spend on inefficient paid channels (TV is dead! Radio is dead! Facebook is, er, dead! Clubhouse is definitely dead) then it makes it easy for those who hold the budgets not to say to the social media manager “you’ve got no budget this year because we’ll be able to go viral.”

[The correct response to this is, of course, yes but the thought leaders are building their personal brand and only need one or two well-paid contracts per month to live comfortably. They’re not trying to increase the sales of the country’s fifth most popular chocolate biscuit brand. At which point the Head of Marketing will probably ask “so how will you increase our sales?” and it all gets a little awkward if the word engagement is mentioned once in the response.]

So let’s repeat this again, in Facebook’s own words: “Click-through [engagement] rate does not correlate ideally to ROAS (Return on Advertising Spend).”

Amusingly, in the same Facebook deck, there’s a McDonald’s case study that attributes between a 2.8% — 3.2% attribution of in-store sales to Facebook and Instagram advertising, which also possibly suggests that Maccas could switch off their Facebook performance marketing spend and probably not see any noticeable difference to the bottom line.

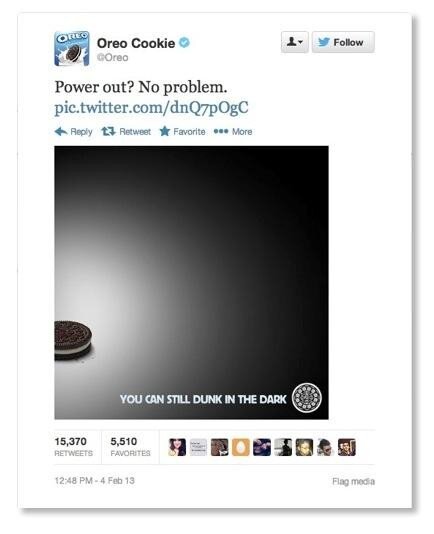

‘Dunk in the Dark’ launched a thousand wrong strategies

That social media engagement doesn’t correlate with sales isn’t really a surprise. Many marketers have been banging this drum for years. It’s worth reading Mondelez’s former Head of Social Media, Jerry Daykin, on Oreo’s 2013 Super Bowl Dunk In The Dark Tweet; one that launched hundreds of social media war rooms, and marketing goals built around ‘virality’.

Daykin, who wasn’t involved in the Oreo activity but was an insider to the numbers, notes that Dunk In The Dark was part of a wider print campaign and the cookie also advertised during the Super Bowl.

Crucially, the number of people who remembered Oreo’s activity, outside of the marketing community, was low, the amount of earned reach, which Daykin estimates to have been between 500k — 1m, was a fraction of the cookies Oreo sells in the US each year, and subsequent Oreo activity that had substantial paid spend behind it was much more effective.

Don’t blame Facebook for the engagement myth

For once, the engagement myth isn’t really Facebook or Twitter’s fault. Facebook in particular has been producing good quality research for several years that’s confirmed this fact repeatedly.

And while it’s true that in the early days of Facebook, it was a lot easier and cheaper to go viral [albeit still not at a scale that would account for Oreo’s total cookie sales], once the blue behemoth throttled reach in the newsfeed to maximise advertising profits the benefits of organic content dropped away quite rapidly.

If anything, social media’s biggest budget efficiency probably comes as a customer service channel, although that’s infinitely less sexy than a viral Tweet, so it doesn’t get quite as many headlines.

Engagement. Because engagement

If you go back further to the days before Facebook had advertising, engagement was one of the very few metrics a social media manager could report back on with any confidence. As somebody who worked in social media around 2008, I was also guilty of this.

It was one of the better metrics we could think of at the time, and it instinctively felt important, because brands being able to talk directly to fans… seems important?

Not many of us at that time were trained marketers either — we generally got our jobs by being good at the internet. And if we didn’t quite understand what these new websites did for businesses, the marketing department sure as hell didn’t either. Had we actually listened to each other, we’d have probably settled on reach being a far more important metric to track.

Again, though, engagement is a metric that refuses to go quietly. Is there a value in cultivating a rabidly loyal following of your brand who hang onto your every word and pithy Tweet? Surely cultivating loyalists is not a bad thing?

And this is where engagement starts wobbling a bit into ‘it depends’ territory. For the majority of big, well-known brands it’s a ‘nice to have’ and can be helpful in some very specific circumstances and campaigns, but it’s possibly not worth spending time or money on for the return back. Largely because you’re probably cultivating and nurturing people who would have either a) purchased your brand anyway or b) have no intention or ability to purchase your brand at any time in the near future.

In How Brands Grow, Bryon Sharp uses the example of Harley Davidson’s largest customer base not actually resembling the stereotypical freedom-loving bikies. They’ve made the brand memorable, but other than not alienating them, Harley Davidson doesn’t need to work too hard to convince them to purchase another Harley.

Similarly, Tesla famously does not advertise and has a rabid online fanbase. But, it also sells far fewer electric vehicles than emission scandal-hit VW, and cannot always fulfil the demand for Teslas due to production line issues.

Unless Musk‘s army of online fanboys all purchase Teslas (that’s assuming the company can actually deliver them), they’re probably not going to be particularly helpful to growing the brand.

Who actually benefits from brand engagement? (Hint: it’s not the brand)

Another example. One of my old agencies was asked to help with the social media strategy for a buildings material manufacturer… Their agency was, at the time, investing heavily in organic social for one of their premium cladding ranges. On the surface, it was easy to see why this approach made sense.

This company produced genuinely beautiful, breathtaking home renovation products that were built for Instagram. Their account had several thousand followers, which was impressive against their competitors. The agency also put a small amount of spend — a few thousand dollars — behind key posts. The engagement numbers looked impressive. In fact, that was just about the only number that cropped up in any reports.

The reality was a bit different. The majority of the followers were in their early 20s and as far away from the target audience as you could get. Unless this was a particularly affluent young homeowner audience, it’s doubtful any of them would have been in the position to buy the product for the best part of a decade.

In addition, many of them didn’t even live in the same country that the product was available in. The number of people the small volume of paid reached was a minuscule fraction of the total homeowner market, and consumers couldn’t actually buy the product as it was only available to sell to trade and most builders knew and asked for it by a different name.

But the engagement metrics looked good.

Is engagement ever good?

A few caveats here. Engagement and earned media is not a total waste for all industries and all companies if there’s a clear strategic goal. TV and sport, for example, when done well, can drive the cultural agenda. There’s also a handful of brands who’ve learnt how to play the algorithm well and have probably been able to reallocate marketing budget elsewhere as a result.

And yes, the likes of TikTok and LinkedIn can still offer impressive organic reach off the back of strong engagement.

For certain target audiences, it makes a degree of sense to invest in content creation for these channels, albeit this is a risky strategy without paid media to back it up or a clear view of what you’re trying to achieve. Clever social marketing — something that Netflix does well — is still complemented by PR and advertising.

Engagement can also be very successful for smaller, growing or nascent brands and products that know how to work the algorithm and quickly scale to a solid customer base or post impressive retention or repeat purchase numbers. Lack of scale among buyers isn’t as much of a problem here.

My wife, for example, has built a small, profitable decorative mirror business largely through Instagram. But she only has to sell a handful of products each month to show a profit after her fixed and variable costs (it helps that she doesn’t discount). So Instagram’s organic reach is entirely sufficient for what she has the time to make and the money she sinks into production and product development.

On the other hand, WARC’s excellent white paper ‘Rethinking brand in the age of digital commerce’ shows that many ‘internet’ businesses built off cheap bottom-of-funnel digital marketing, including organic social, hit a point where they cap out and literally cannot grow any further without investing in brand as well as performance. Engagement serves them perfectly well until they hit their natural growth ceiling.

Source: WARC/James Hurman, Brand As Future Demand (August 2021)

But at the end of the day marketers, like people, can be quite irrational. Even when Facebook types out the words that engagement does not cause sales, their account managers will still be trying to explain the same finding next year, and the year after, and the year after that.

Because as long as there are thought leaders who use engagements to promise untold marketing riches, there will always be marketers who go all in on an earned strategy. Budgets are reallocated, targets become unachievable, and tactics and outputs will become a series of unlinked and unliked executions commissioned in the name of engagement.

Occasionally, just occasionally, one of these executions may go viral. Once in a blue moon, a brand may go beyond viral and actually enter the realms of cultural conversation, like Weetabix’s baked bean Tweet. And for those who are a mixture of lucky and well planned, heavy engagement may produce a very short term spike in sales as a result of a temporary increase in salience.

But that’s a best-case scenario. As for every brand that “does a Weetabix”, there will be hundreds of others churning out mildly engaging content with questionable results, and still having awkward conversations with the people who hold the marketing budgets.

=====